Intersecting Paths | A Conversation with the Curators Behind 'Here'

Posted on | Updated

The artists and Âé¶ṗÊÓÆṁ students behind the recent Aboriginal Students' Exhibition talk politics, inclusivity and the challenges of being Indigenous in a settler institution.

Diane Blunt, Megan Jensen and Sydney Pickering all agree: the name came first.

Here.

Sitting in the Aboriginal Gathering Place, the artists and Âé¶ṗÊÓÆṁ students (and three of the four curators behind this yearâs Aboriginal student art show) say that once theyâd landed on that title, they knew it was right. (Hereâs fourth curator, Kelsey Sparrow, was unavailable for interview.)

âThe name was born from everything that was going on, everything thatâs still going on now,â says Diane (who is of Ojibway and European ancestry, and a member of the Kawartha Nishnawbe First Nation).

She points to some of the current issues involving Indigenous rights within Canada, including the local, national and international showing of solidarity with members of the Wetâsuwetâen nation and other Indigenous peoples who stand in opposition to the "current environmentally invasive and destructive projects" being built on unceded territories; the ongoing tragedy of; and the broader and arguably failed project of reconciliation in Canada.

âWe wanted to be relevant and react to whatâs happening. It was like, âWeâre HERE,ââ she exclaims, bringing her open palm down on the table in emphasis.

Sydney (who is of Lilâwat and European ancestry and a member of Lilâwat Nation) notes that the decision to refer explicitly to political issues was one they all had to warm up to.

âI remember we wanted to stay away from that, initially,â she says. âBut in the end you canât ignore these things. At the opening we said, âWe have to bring this up,â and in our remarks we said, âWe stand in solidarity with our Indigenous neighbours.â Our lives are inherently political.â

Diane agrees, adding the show âended up being quite political,â even though their curatorial call for submissions had been an open one.

âWe didnât call for that kind of work, but thatâs what came up,â she says. âItâs on everybodyâs minds. Itâs an emotional thing. And itâs always an undercurrent of our lives.â

Megan (who is of DakhkÃḂ Tlingit and Tagish KhwÃḂan ancestry, and a citizen of the Carcross/Tagish First Nation) reflected that, in retrospect, there was probably only a slim chance the show could have turned out any other way â especially with the issue of Wetâsuwetâen sovereignty front and centre in communities across the country.

âI think we all felt like we couldnât not do anything. This is something so prevalent in our lives, and we were considering the other artists and the emotional labour they may be undertaking,â she says.

âAll of our hearts feel heavy being at the protests [in solidarity with Wetâsuwetâen hereditary chiefs]. But then weâre all emotionally heavy when weâre not able to be there. The way I felt was that this show was a way for us to contribute to the cause. This is our way to give more voice to those that are silenced.â

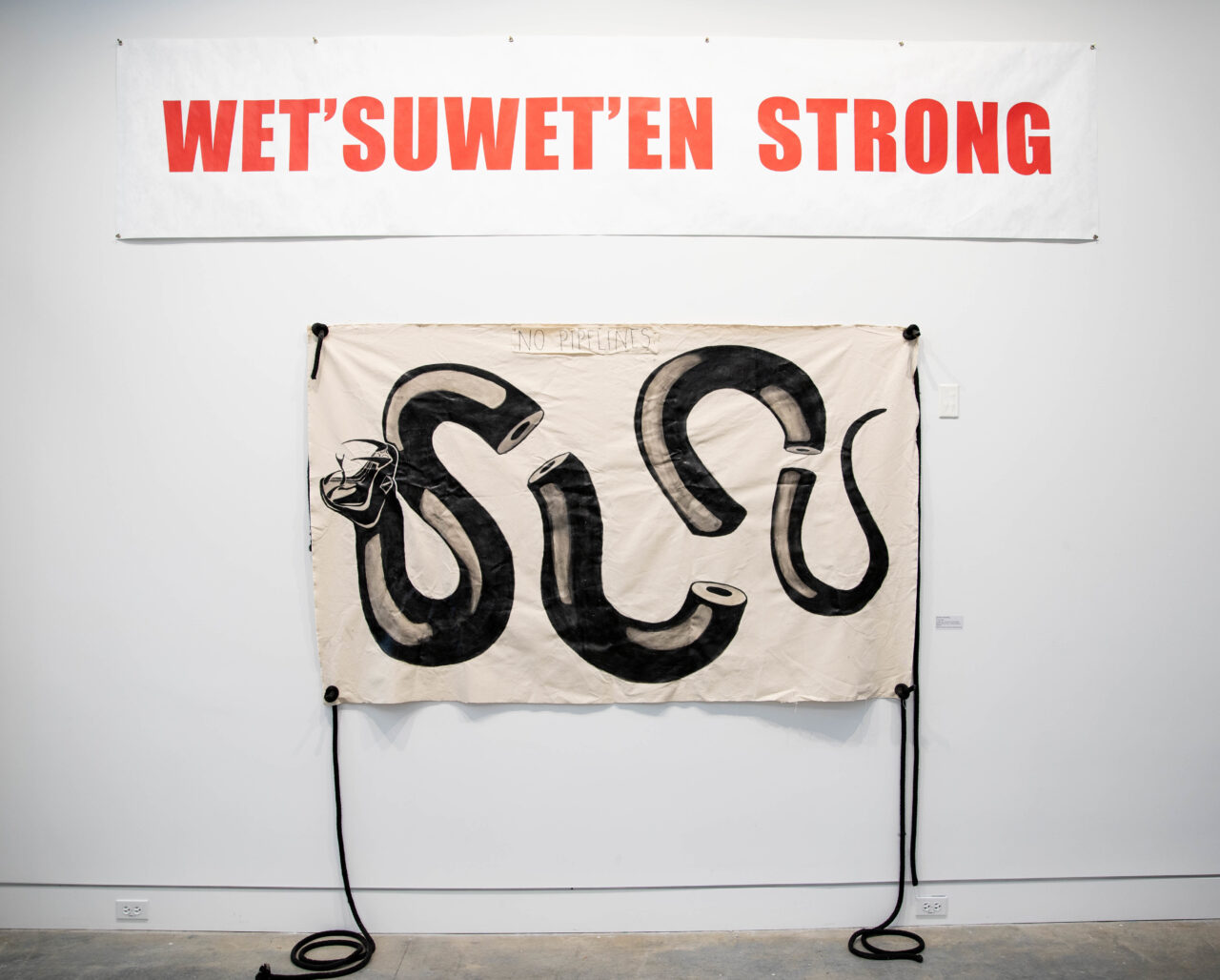

Diane, Megan and Sydney each have work in the show as well. Sydneyâs

work includes an austere anti-pipeline banner that was used during

protests in solidarity with the Wetâsuwetâen people, and an installation

of brain-tanned deer hides she made with her community in Mount

Currie as a representation of her reconnecting with her ancestral lands.

Dianeâs work includes woodland landscape paintings

incorporating birch-bark bitings which, she notes, take on political

undertones when viewed through the lens of the exhibitionâs broader

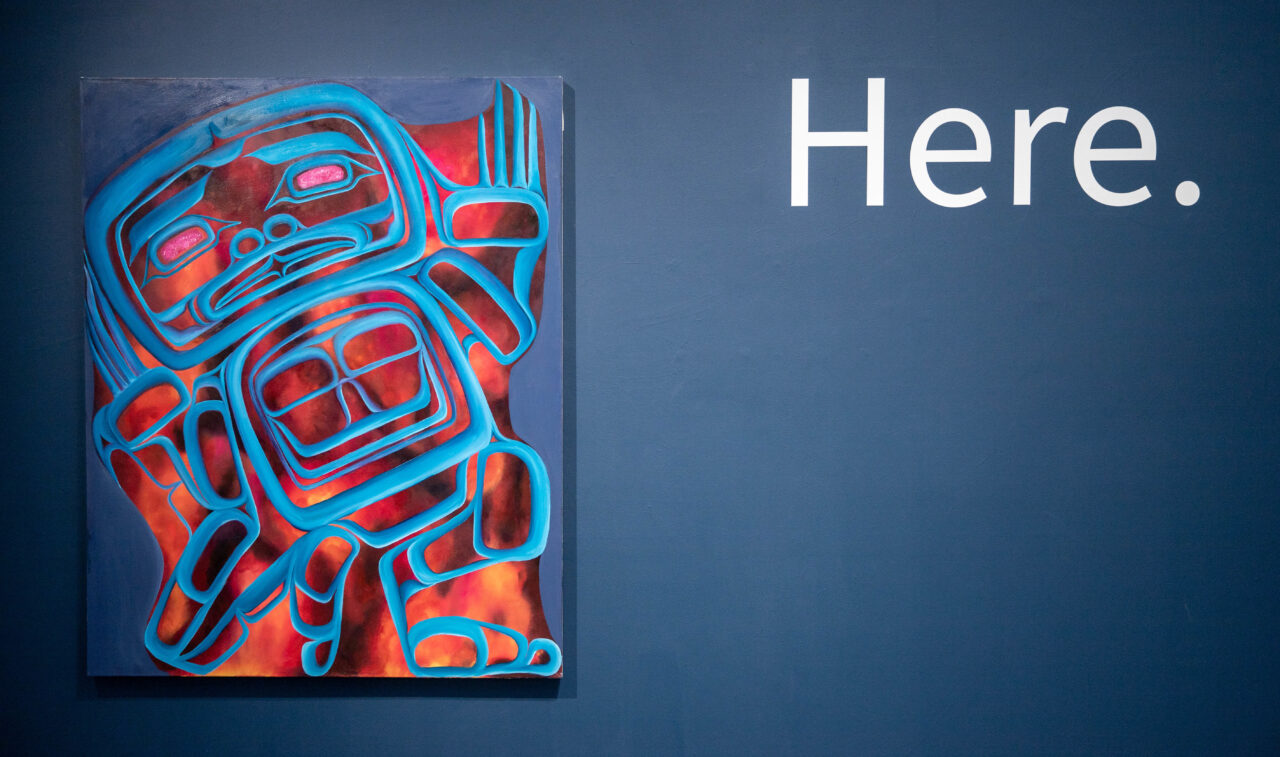

context. Meganâs work includes the Northwest Coast formline painting at

the entrance to the Exhibition Commons, on a wall painted a dark, slate

blue that echoes the colours of the painting itself. The figure in

Megan's painting appears to struggle within the confines of the canvas,

enacting a push-and-pull tension with the edges of the painting itself.

âAs Indigenous artists, we all to some degree experience these tensions during our time in university, and that expands beyond these walls as well," Megan says.

Sydney reports having struggled with some fundamental questions in undertaking an exhibition at a time when attending demonstrations and solidarity actions feels like an urgent obligation.

âI feel conflicted, sometimes, taking the time to be in these actions and then coming back here, to the school,â Sydney says. âItâs such a different environment. It feels like, is visual art going to have an actual impact? Or inform people?â

Megan and Diane say Sydneyâs questions reflect a deeper struggle to square the idea of being an Indigenous artist in a settler institution. This status, they note, can lead to situations where theyâre asked to do the work of âbeing Indigenousâ â a semi-coercive expectation that the Indigenous person in the room will act as teacher for groups of people who may not understand Indigenous history or contemporary politics. Here, they note, is in many ways a response to some of these challenges.

âFor me,â Sydney continues, âbeing an Indigenous artist partly means making that decision about how much information youâre going to give, how much youâre going to let your audience in, and how much youâre going to allow them to put their interpretations on you.â

âThatâs an act of reclamation,â Megan adds.

Ultimately, reflecting the diversity of Indigenous experience at Âé¶ṗÊÓÆṁ was the goal the curators had most hoped to accomplish â and proudly fell theyâve achieved.

âWeâre all at different levels all the time,â Diane says. âSome of us are really strong politically, some are not. Some are really strong in their culture, some are not. Some are just dipping their toe in, approaching it for the first time. Thatâs whatâs so great about the Aboriginal Gathering Place: here, they embrace all of us.â

âWhich all circulates back to Here,â Megan adds. âNot all of us are on the same path but weâre all here. And all of our paths intersect because weâre here. But weâre our own distinct people, and weâre all individuals. And we wanted to honour that.â